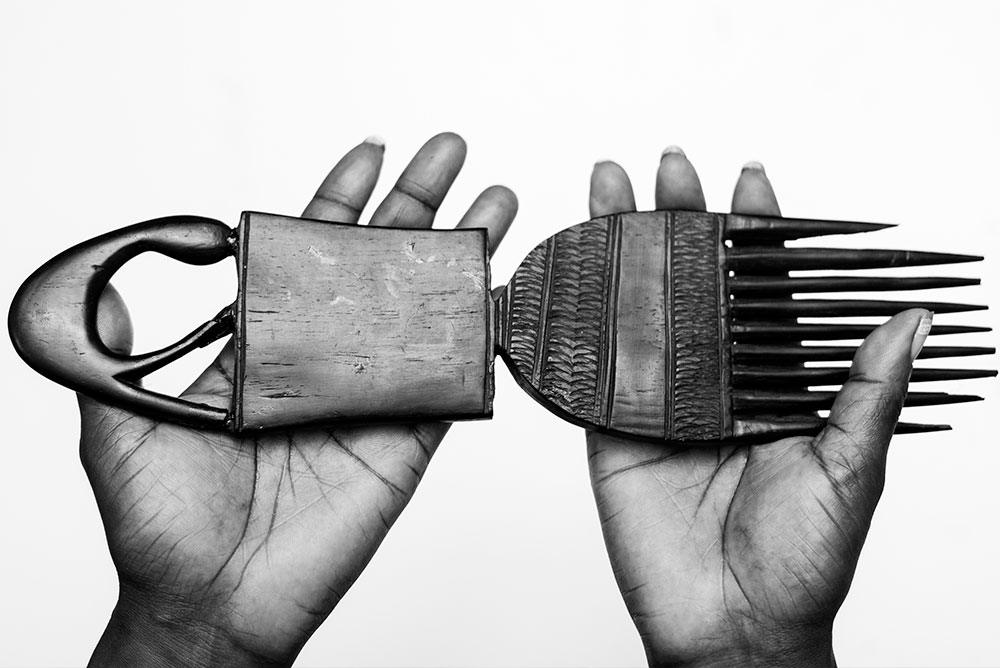

Traditional hairstyles and drums

Afro culture celebrates its traditions

Music, gastronomy, dances, braids and hairstyles are part of the cultural practices that Afro-descendants bequeathed to the Colombian nation while rehearsing routes of resistance and freedom.

Tenderness is a grandmother braiding her granddaughter's hair on a Sunday afternoon on a street of San Basilio de Palenque; A town of northern Bolívar, in the Colombian Caribbean, founded by enslaved Maroons who fled the port of Cartagena de Indias. The beat of the drums can be heard there since the 17th century and, perhaps, also since then do grandmothers comb their granddaughters' hairs while telling stories about resistance.

Tenderness can also be two young black women on a Friday at noon, on the day before a party in Guachene, north in the department of Cauca in the Colombian Pacific, taking turns while trying different hairstyles on the patio, under the shade of a wild cashew tree. In Guachene, a city inhabited by Afro descendants since the times of the gold rush and the working haciendas, black people have braided their hair.

These postcards of tenderness are replicated daily in several areas throughout the county. Colombia has a wide variety of regions inhabited by people of African descent. Their music, gastronomy, dances, oral tradition and hairstyles broaden the experience of visiting our country. Multiple Colombian fairs, festivals, and carnivals have a distinctive African touch.

Memory hides behind these scenes: those who tell what was long ago told to others, they speak of maps drawn with hair by expert braiders on the heads of girls and women and later be used by Maroons as escape routes. The wise claim hair in the beginning, hair was at the core: Alonso de Sandoval, a sensible priest and Jesuit evangelist who spent a large part of his life working on a treaty on the characteristics of Africans brought to Cartagena (America’s main slave port), said that one of the clearest signs to identify them was the way they wore their hair, with which they made — according to the priest— "thousands of pleasant inventions."

The poets who sang to the memory of those enslaved also said that men and women would hide seeds in their large afros and, upon the chance, shake their heads to spread them in lands where freedom could bloom. Others claim the abundant hair helped slaves hide small pips of gold from the mines they worked, with which they would later buy their freedom.

Along with the drums, hairstyles are the main communication tool for the Afro community in the construction of their national identity.

The truth is that routes and complicity of your hair and its design exists from long ago. And today, Afro descendants in several regions of Colombia are increasingly aware of the importance of this legacy. They take it as a component of their identity, but now their hair isn't meant to hide, it is meant to be displayed and now tell a different story.

This route of pride, of beauty without complexes or impositions, can start in San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina, the insular territories in Colombia's Caribbean Sea.

There, in those isolated lands of barracudas and green moons, of pirate stories and to the beat of the musical rhythms of mento, reggae, socca and calypso, you will find people moving in harmony with their dreadlocks, raizal women weaving dreams on the head of some tourists and young people in their daily work wearing hairstyles that remind us that the diaspora didn't happen so long ago; all of them joining other black people from the Greater Caribbean.

Drums, braids and afros in Palenque and Cartagena

In this population, declared by UNESCO as a World Historical and Intangible Heritage in 2005, hairstyles are as common as the pride founded by the Maroon Beknos Bioho in the 17th century, when he developed a sovereignty without shackles around in these lands.

In every home someone combs and braids hair with the same ease as the one used to pile grain, sow yams, prepare preserves and milk cows - the peaceful skill with which things that have always been there are done.

It is also natural, as well, that the only beauty parlor is called "Reina del Kongo" (Queen of Kongo) and that its owners take care of giving an ancestral vibe to what they do. They braid to honor the routes of freedom, and their works have names as neat and tidy as the designs they stamp on their clients heads: hundidito, tomate, puerca paria, African innovation (also known as cacheta), these are just a few joyful denominations of a skill that has its own history

In this land where drums resonate with life, the Palenque Festival of Drums and Cultural Expression has been held annually for over twenty years to celebrate the gastronomy, music, dance and hairstyles as ancestral means of communication. Under the blue October skies, the traditions inherited from Africa come to life, adapted to the new places and preserved by committed generations who have placed the echo of their essence on the drumhead.

About an hour away from Palenque, we find Cartagena de Indias its true historical memory: that of the African diaspora. A while back, black neighborhoods imposed their style by making a statement through people's hair: braids, haircuts, abundant afro, messages of vindication and an entire education on how to care for it roam the streets, schools, universities, offices, cultural events and daily life.

Afro-Pacific Routes

The route, as in the old days of slavery, traces the Atrato River to enter the Colombian Pacific. The difference is that nowadays those territories are traveled, not only to find evidence of a past that infamously condemned human beings to forced labor, but also to have fun with those traditions of resistance, that reassured the right to exist and to an identity through the ways of combing their hair.

Those who have dedicated themselves to creating an inventory of hairstyling and braiding practices in the region don't hesitate to highlight the peculiar styles used in Andagoya, a mining town in the department of Chocó the dextrity of those who work in Robles, in the department of Valle del Cauca and in Villa Rica, in the department of Cauca , a little further south from the Pacific region in Colombia. Braids, twists, screws, weaving... all sorts of techniques for the hairdressing roam around alternative catalogues that people create, and in the organization of events and festivals to reward the best works. At the same time, ancestral knowledge associated with the plants used to take care of hair: aloe, artemisia, peppermint, rue, mate and the bark of the guacimo tree combined in the cosmetology created over past few years to preserve the natural quality of Afro hair.

In Istmina, Choco, a themed hairstyle contest is celebrated, associated with the festival of the to the patron saint festival

in favor of the Virgin of Mercy, held in September, in which the geographic and cultural values of the region are highlighted.

In September and until the end of October, the city of Quibdó, capital of Choco, the banks of the Atrato River, becomes a mass of people dancing in the streets to the same beat. This is the festival of San Pacho, a celebration in honor of Saint Francis of Assisi that has been held since 1648 and that, in 2012 was declared Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO. Music, floats, dances costumes and the conscience of a community who used the festivities as a catharsis to reinvent them-selves in the midst of the daily anguish of work and life, without knowing, perhaps, that someday it would be built one of nation’s most important

cultural events.

In Buenaventura, the main Pacific port in Colombia, where there has always been a strong influence of the black movement aesthetics from the United States, black men's hairdressers in the neighborhoods compete for best hairstyles. These settings are meeting and social spaces for young people, and with migration towards big cities in the country these same practices have migrated, as well, to the beauty dynamics in Bogotá, Medellín and Cali.

For the past fifteen years, every June, the festival Weaving Hope is held in Cali, in which the cultural identity of the Afro-Colombian, Raizal and Palenque population is reaffirmed; the right to difference and diversity is celebrated and local knowledge is set for dialogue with other countries in America who are also recognized by the common memory of the diaspora. The capital of Valle del Cauca and main urban center of the Pacific Region is also home to one of the cultural events that has grown the most in past decades and that attracts the largest number of tourists each year. This is the Petronio Álvarez Pacific Music Festival, which has not only become a reference point for a black music in the region, but also condensed in the same place, in a festive and contagious way, the most complete cultural expressions of the afro-descendant population.

It must be said that many paths had to be walked to get to the place we are now. In a society that approves of slavery, identity can be turned into stigma.

The hair that identified them also condemned them; the the mockery grew abundant- like bushes of hair. By the end of the 1960s, ethnographer Luis Florez published a lexicon detailing the different terms Colombians used to refer to human body parts. In his research, Florez found little over fifty terms to refer to Afro-descendant hair. All of them with a strong derogatory connotation. Achicharronao, cadillo, churrusco (spring), duro (stiff ), pelicerrao, tornillo (screw)... are some of the terms used to refer to hair. But People, with the same ability the weavers use to braid hair, learned how to turn it around, to escape stigma, to turn it into a source of pride.

Perhaps the grandmother, who on a Sunday morning diligently combs her granddaughter’s abundant hair in the streets of San Basilio de Palenque, always knew. And she had the patience to braid the identity and the beauty that some members of this diverse nation now wear with grace.

Text by Javier Ortiz Cassiani